In the Fall of 2000, after the panic of the Y2K scare and the collapsing dot-com bubble, I sat in front of a Macintosh desktop computer running a program called HyperCard. I created stacks of virtual cards which I, or anyone at the computer, could click through to freely explore. I recall that navigating my stack from first card to last made little sense. Each card was a fragment of some concept I was thinking through with the program. Linking cards was my first impressionable encounter with the concepts of intertwingularity[1]—Ted Nelson’s expressive term to describe the sense that there is no neat organization of knowledge: EVERYTHING IS DEEPLY INTERTWINGLED.

It was soon after this experience that I started to discover HTML. Programs like Microsoft FrontPage helped me author hypertext through a WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) editor. Composing a “page” was done by adding elements to what seemed like an infinitely tall and wide document that I could assemble like Word Processing software and drawing programs. Like HyperCard, these programs considered the composing of HTML to be an open-ended practice—software with “low floors and high ceilings.”[2] They started with the simplicity of editing elements on a page and allowed users to make the (often considerable) transition to expressing those objects in written code.

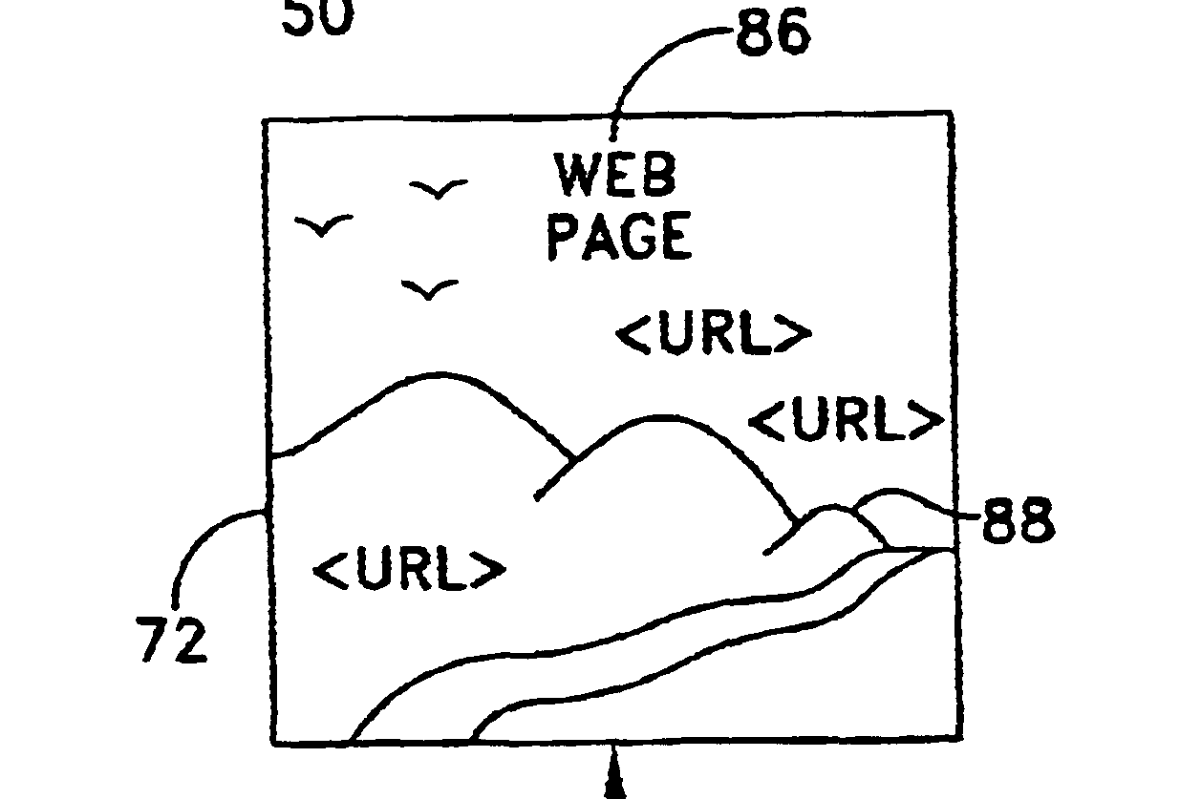

The act of assembling a website using these pieces of software felt different from learning a programming language. Content was authored by inserting elements on a page and a layout was clicked and dragged into existence as a container for words, images, and links to other pages represented as files and folders connected together. In contrast, view source was the textual space where syntax was laid bare.

The ability to view source was introduced in the mid-1990’s through web browsers like Netscape Navigator 3.0, released in 1996. Clive Thompson’s book Coders notes that early versions of Netscape Navigator introduced view source as a “fun way to let people surfing the web to see this code, if they wanted to.”[3] At the time it was called “Document Source,” and located under the “View” dropdown menu of the running application. When clicked on, a window would open showing the raw HTML of the page you were currently viewing. The window displays a disorienting stream of text with traces of visible content, files, and links that feel like encountering a new language.

“Every single web page you visited contained the code showing you how it was created. The entire internet became a library of how-to guides on programming. If you wanted, you could cut and paste that code into a new file, change a few elements, and see what happened.”

On my personal websites view source meant being able to adapt and remix ideas. Like drawing a map, elements and pages acted as landmarks in the browser to be navigated between. As a self-initiated learner, being able to view source brought to mind the experience of a slow walk through someone else’s map.

This ability to “observe” software makes HTML special to work with. In particular, it’s sense of “transparency” as Clay Shirky wrote in April, 1998, numerating on what makes for “good” software:

“Good tools are transparent. Web design is a conversation of sorts between designers, with the Web sites themselves standing in for proposal and response. Every page launched carries an attached message from its designer which reads "I think this is a pretty good way to design a Web page", and every designer reacting to that will be able to respond with their own work”[4]

I brought these early websites with me from computer to computer on 3½-inch floppy disk—like an improvised sneakernet[5] before using free to low-cost servers—and opened them with the installed browser to share what I’d made with friends. In the moment, seeing something you had made on someone else's computer felt like a gift. It became an important gesture in what I was learning, the feedback loop of creating a website and being able to view it on another computer and continuing to change it over time.

I sometimes wonder what happened to those original floppy disks. I’m sure the websites on them would continue to display as they had in 2000 if they found their way to a computer again. HTML, browsers, and the protocols they work with are incredibly durable ecosystems. You could open these websites as a series of plain text files using an editor. Alternatively, you could use the browser’s view source feature; a capability that allowed me to learn how other websites were created by seeing markup and what is rendered in tandem.

View source is still present in most web browsers as a menu option or a standardized address that could be typed in the address bar. In 2011 the IETF[6] registered the pattern of using “view-source:https://…” to show the source code of a given page in plain text[7]—a view preserving much of the author’s formatting and presence. This can be in the form of comments, the traces of unused elements, and the idiosyncratic presentation of preformatted text.

I often wonder what would happen if the ability to view source was made to be more present in the browsing experience—a gesture, or invitation, to see what and how a site is composed. What if the structure of an HTML file spoke further to the content being rendered? If an element had an inner voice, what would it say? Can this history and context be expressed in the way we interact with and learn from view source?

“Markup works similarly in the formulation of historical (electronic) texts. It has its own history (the versioning of SGML/HTML/XHTML), its own grammatical lineage (the development of some tags over others), its own narrative (the archaeological layers of comments attached to shared code), and even its own politics (language choices, browser compliance, and the choice to share code or retain its mystique as the writing of an invisible professional). Markup thus becomes a kind of ghostly writing dependent on context and history, rather than merely a means of formatting text.”[8]

The ability to see marginalia through view source could be a place for this to happen. We can draw parallels with the physicality of a book—when you see a page in a book you are sometimes able to see the next page depending on the paper and the way it has been printed. I wonder if view source could be a similar gesture, a website being a porous material where its creation can be viewed at the same time. This idea draws its parallels to book publishing and the use of hidden markup from Helen J. Burgess:

“Long before the magical moment of “View Source,” print and book producers were already using their own forms of hidden markup: the symbols written on texts that contained instructions or marked points for the purposes of textual reproduction. These printers’ marks are the antecedents of today’s markup schema: they are marking up manuscripts in the same way we mark up electronic texts.”[9]

“The HTML tags we can see in our browser’s “View Source” window are akin to early printers’ marks: they are not readily apparent, but they can be read if we know where to look, in the process of flipping back and forth between page and source code.”[10]

This brings to mind J.R. Carpenter’s writing on A Handmade Web where a relationship is made “between handmade web pages and handmade print materials, such as zines, pamphlets, and artists books.”[11] Pages made by hand, the presence of a person in motion, manipulating a medium as an act of self-publishing as well as an act of allowing others to contribute.

Our cursors are often gliding from one page of the page to another in the browser window. We take for granted the ease of this interaction as each element commands some level of attention by us, the viewers. A texture is created not just by the final rendered form, but also by how the layout is constructed, by the underlying language an author imparted in constructing these documents.

I think of this as how Alexander Galloway describes the work of net artists, Jodi (Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans): “The resulting aesthetic is, in this way, not entirely specified by the artists’ subjective impulses. Instead, the texture of code and computation takes over, and computing itself—its strange logic, its grammar and structure, and often its shape and color—produces the aesthetic.”[12] For Jodi this consideration extends beyond what is shown in browsers, it includes the underlying protocols, standards, and applications that enable much of what we consider to be the internet today.

Examples drawing on this computation and code aesthetic include ASCII Town[13] , a workshop influenced by concrete poetry and typewriter art. Participants created imaginary dwellings referencing the rich histories of ASCII art[14]. And Evan Roth’s All HTML[15], a page containing every HTML tag in alphabetical order. Browser default elements crudely composed in the browser window become fully legible when view source is used to observe how the file is constructed.

From the book, to HyperCard, to the internet, information is encoded and “marked-up” as instructions so that it could be rendered into their intended form. View source is a gesture that sits somewhere in between these moments, another space where a visitor could reside with its own aesthetic qualities and materiality. The space is both complementing and in tension with being interoperable with a browser—the precision of syntax in determining if syntax is “valid” or not to the minutiae of comments left a HTML file for us to discover and trace its creation.

In the end, view source is a reminder that software is a human activity with all its nuance, and mundanity, laid bare waiting to be viewed in our browsers. View source is a slow space, a gesture to see the presence of a person, and a space to come back to.